-Donna, we’d love to hear your story and how you got to where you are today, both personally and as an artist.

I have always been an artist. I was just not a very good painter or illustrator compared to my contemporaries. I found photography when I was twelve years old and used an old Rolliflex to photograph throughout high school. I studied under photographer Walter Scott while in high school, but by the time I got to college I knew that I needed a consistent income after graduation, so I changed paths and became a creative director before coming back to photography five years ago.

I really could not suppress my artistic nature any longer. I was at a place in my career where I was successful, but not very happy. Photography is how I see and without it, I am blind. It is a way that I navigate life and understand my role in the world.

-What did it take to find and own your voice in your art?

Teaching and learning the basic techniques of photography or filmmaking are very straightforward, but learning to be an artist cannot be taught, it can only be learned.

To learn more about who you are as an artist and what you want to say, often involves someone asking you the right questions. These questions come from mentors, other artists, yourself, and all of the above. Regardless of who asks the questions, only you have the answer. The exploration and discovery period, where we find our voice as artists usually happens over time, as we continue to create work that becomes more and more personal, rather than just something imitated or found.

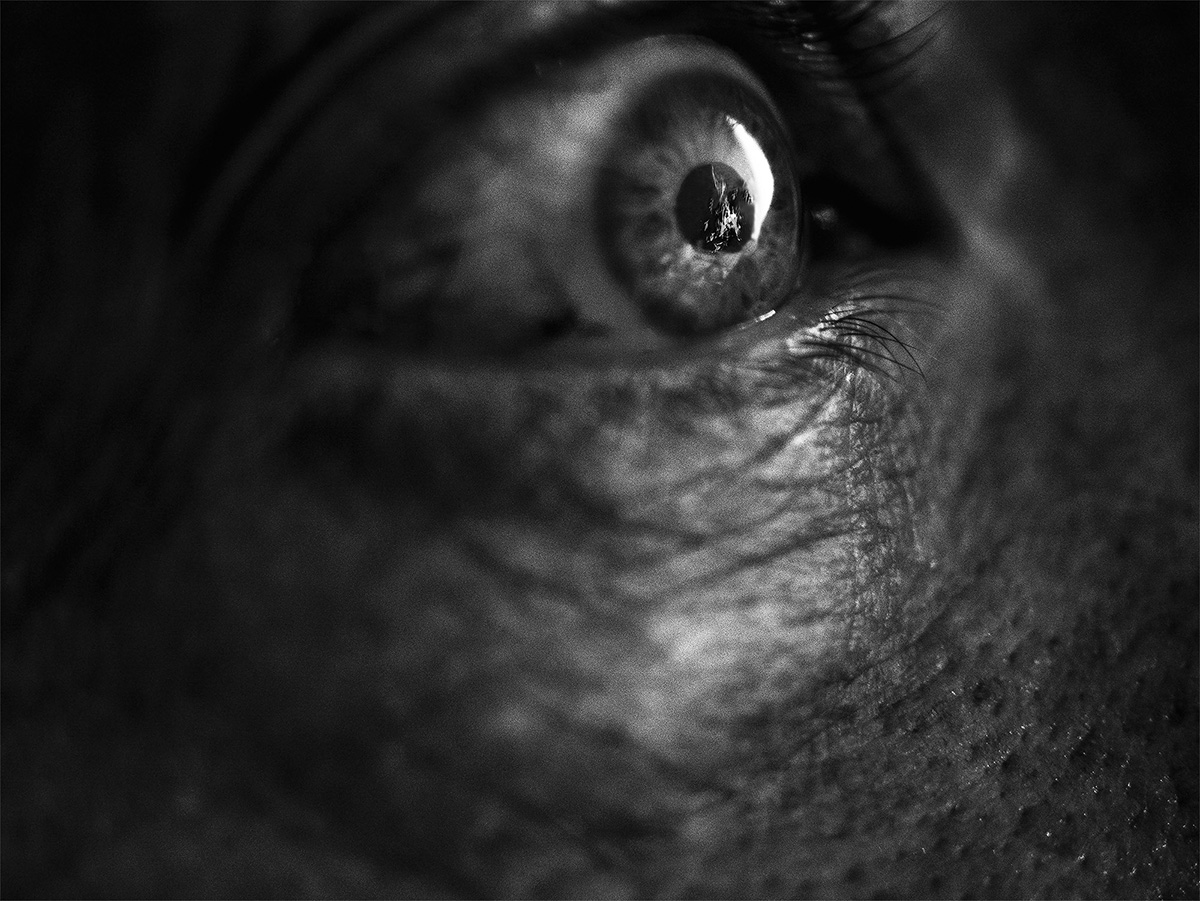

Owning my voice, for me, means that the visual syntax of the images communicates in a way that allows the viewer to see, not only the subject in an image, but also themselves.

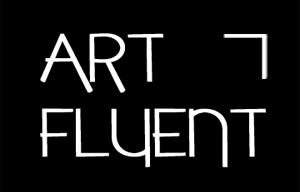

Much of my work deals with liminal space and the subject within it. It represents that moment in time and space where the viewer sees themselves and the other (people or things not like them) at the same time, allowing them to feel empathy for the subject. Muscogee from my series Indian Land For Sale is a great example of liminal space in my work. That particular series was the first time that I had embraced my heritage in a project, which enhanced the organic grounding of the style and the narrative.

My ability to slip outside of the rigidity of “the norm” by creating these unstable images in which the subject operates through two points, in a kind of in-between space allows me to own that space and time by allowing for a visual kind of parapraxis to manifest. The work is allowed to create itself, in camera, with little to no postproduction. Through the use of manipulated exposure, motion and light/shadow influence, it crosses the threshold where subject and object become one. A transcendent moment is created, like a slip of the tongue, when a repressed truth is revealed to the viewer.

-What are the questions that drive your work?

Is my work engaging? Will it be captivating enough for people to want to interact with it?

Do these images make you feel that something is not quite right?

Will this work allow the viewer to know what they didn’t know before, and explore expanded possibilities through interpretation?

How will the process used in creating the work inform the narrative?

Does this work create empathy in the viewer for the subject (the other), and can that empathy help to re-frame history?

Does the subject of the work exist in an ambiguous space? I use abstraction, done in various ways, to cause an inner reality to be exposed when the appearance of certainty is eroded. When things shift from secure and safe to a reality that is indeterminate is when forms detach themselves from their literal nature and are then capable of isolating the most significant expression within their meaning.

How is time affecting the idea of self for the subject and the viewer? There are three roles of self in time - the self in the past, present and future. When time stops literally, as with the pandemic, is there an alienation of self? What does that look like? Can that same alienation of self be created through oppression? What does that feel like and is that being communicated visually?

-Talk to us about knowing what and how to share, and when not to. Walk us through your editing process.

I generally edit images on the spot; unsentimentally cutting off and throwing away those frames that don’t give me an emotional charge. However, over time I have discovered that even when the photographs aren’t what I want, looking at them is instructive.

Like the great Robert Frank, one of my influences, I try to quickly eliminate the images I don’t “connect” with, but use them as a tool to better understand what my good images feel like and how they inform each other in a series. What you reject is just as important as what you show in that regard.

When Robert Frank shot The Americans, when trying to make sense of a vast accumulation of work, Frank knew that just as he photographed by process of elimination, he needed to also edit the work prints that same way and did so in order to “come into the core” of what he wanted to express. That is very much how I approach my editing process.

-What’s the best way for someone to check out your work and provide support?

Great ways to view or purchase my work online are through my website donnagarcia.com or on Instagram @donnagarcia23.

Indian Land For Sale will be exhibiting at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston, MA from May 26, 2021 – July 9, 2021.

Statement

PROJECT ABSTRACT - In 1830, the United States government, led by President Andrew Jackson, forcibly relocated native populations east of the Mississippi in order that white farmers could take over their land. The event led to a conveniently forgotten genocide, and the extinguishment of the Indigenous narratives from American history.

My series Indian Land For Sale, attempts to recreate the horror of this event from the perspective of the native tribes. My images serve to replace what has been lost from official historical archives and seeks to sound an alarm, as the federal government, in 2020 and beyond, continues its attempt to revoke ancestral land from protective trust.

SERIES STATEMENT: INDIAN LAND FOR SALE

In 1830 the Indian Removal Act was enacted throughout the American East Coast.

President Jackson declared that Indian removal would "…Incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier. Clearing Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi of their Indian populations would enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power."

Systematic hunts were made to force indigenous people from their ancestral land.

A Georgia volunteer, later a Colonel in the Confederate service, said, “‘I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by the thousands, but the Indian removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

Following the signing of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 the American government began forcibly relocating East Coast tribes across the Mississippi. The removal included many members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations from their homelands to “Indian Territory” in eastern sections of the present-day Oklahoma. It was a 1,000-mile walk and took 116 days from Georgia, walking all day and only being allowed to stop at night to bury their dead. This is what we now know as the start of the Trail of Tears.

Between the years of 1830-1838, 100,00 indigenous people were “removed” from their ancestral lands. Although, no one is sure the exact number, approximately 21,700 Muscogee and approximately 16,500 Cherokee were removed by 1831.

Not all indigenous people left in 1830, specifically the Cherokee. Many stayed, thinking that they would be allowed to live peacefully or have the ability to fight back (actually winning several legal battles against the removal order). However, the Georgia State government and Andrew Jackson, had plans for their land. Flyers began to circulate hailing “Indian Land For Sale”.

White farmers flocked in droves to auctions of indigenous, ancestral land that was still, up to 1838, being occupied by its native people.

It was in 1838 that 7,000 US soldiers in Georgia enforced a final evacuation. The Cherokee, Creek, Shawnee and Choctaw villages were invaded and the people were forced to leave, at gunpoint, with only the clothing on their backs.

For the few who resisted, approximately 1,800, died while imprisoned for refusing to leave.

Historians such as David Stannard and Barbara Mann have noted that the army deliberately routed the march of the Cherokee to pass through areas of known cholera epidemics, such as Vicksburg. Stannard estimates that during the forced removal from their homelands, 8000 Cherokee died, about half the total population. Half of the Choctaw nation was wiped out and 1 in 4 Creek.

A Cherokee survivor of the trail told her granddaughter, “The winter was very harsh and many of us no longer had shoes. Our feet froze and burst, as we left bloody footprints in the snow. We were not allowed to stop to bury our dead. Many mothers carried their dead children, miles, until we stopped at nightfall. All night you could only hear digging.”

The deportation of indigenous tribes along the Trail of Tears was an act of genocide that has been conveniently forgotten today. But, on March 30, 2020, the federal government of the United States revoked reservation designation for the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe and removed their 300 acres of ancestral land on Cape Cod from federal trust. This most recent government land grab raised grave concerns among indigenous advocacy groups across the country that all tribes could now be at risk of removal– again.

Bio

Donna Garcia is lens-based artist, filmmaker, curator, art director and educator based in Atlanta, Georgia. Originally from Boston, her work often illustrates a semiotic dislocation that has been organically reconstructed in a way that gives her subjects a voice in the present moment; something they often did not have in the past. Her images rise above what they actually are and become empathic recreations in a fine art narrative. She often utilizes self-portraiture with motion to provide an indication of the other in her work; a surplus threat to the perpetuity of our modern day grand narratives in defining elements like gender and race. Her work reveals the self as a stronger potential that does not correlate with a bounded social order and my subjects don’t abide by rules. There is a strong presence of future and coming into being, which allows these images to pull the viewer forward through recognition and interpretation, into a new sovereignty and an expanded way of knowing.

She has worked as an art director for Ogilvy, NYC, an adjunct faculty member at the Art Institute in Atlanta, a contributing editor of LENSCRATCH and founded the Garcia | Wilburn Fine Art Gallery, where she directed and curated a number of influential exhibitions highlighting the work of emerging and established artists. Garcia and her partner, Darnell Wilburn launched the Modern Art and Culture Podcast. In their first year, they were chosen to become the official podcast of the Atlanta Celebrates Photography Festival, the United States largest, month-long photography festival, held annually in October.

She has exhibited internationally and has had her work published worldwide (see donnagarcia.com). She is a 2019 nominee of reGENERATION 4: The Challenges of Photography and the Museum of Tomorrow. Musee de l’Elysee, Lausanne, Switzerland. Emerging Artists to Watch.

Donna Garcia has a Master of Fine Art from the Savannah College of Art and Design and a Master of Science in Communications from Kennesaw State University.